Article Written By Kyle Ringo for The Express-News

Article Written By Kyle Ringo for The Express-News

When longtime San Antonio area sports fans debate who the best athletes the area has produced throughout history are, a variety of names are bound to be mentioned, but a man who might belong at the very top of that list could be completely overlooked now because so few of those who actually saw him play are still alive to recall his talent.

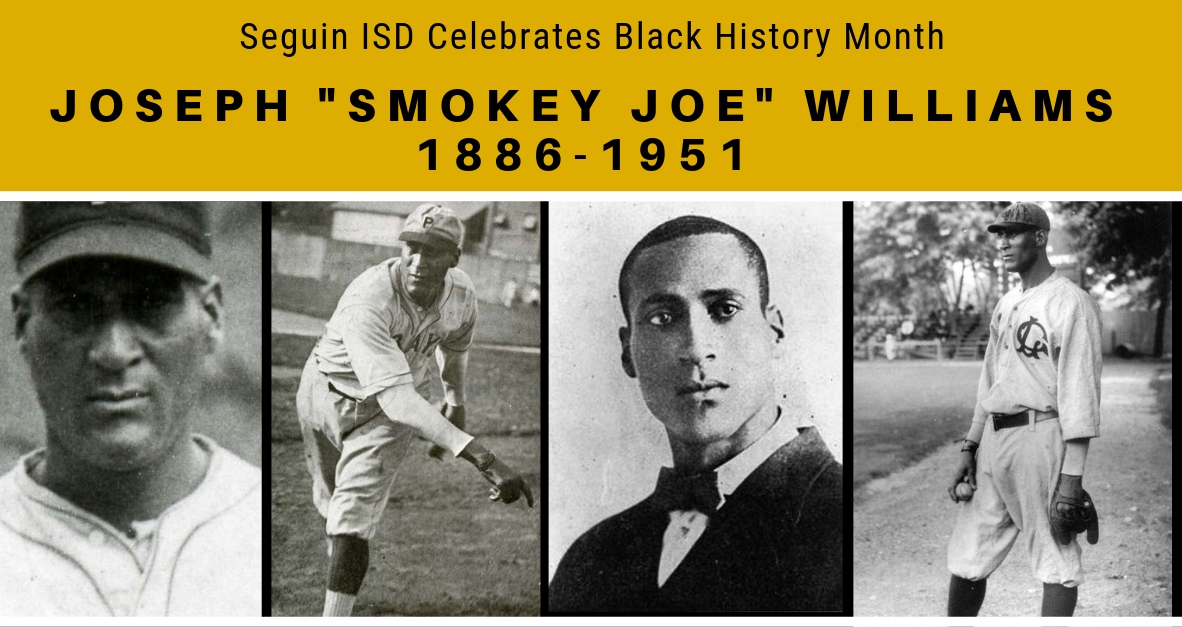

Fortunately, the National Baseball Hall of Fame saw to it that Smokey Joe Williams wouldn’t be forgotten when it inducted him into its ranks in 1999 along with legends from the modern era such as Nolan Ryan, George Brett and Robin Yount. The honor came 48 years after Williams’ death.

Williams is said to have been born April 6, 1886, in Seguin, though no official birth records exist. In those days, Seguin was a segregated small town a day’s travel east from San Antonio. Now, Seguin is the home of the baseball diamond bearing his name in the town where he grew up as the son of a former slave.

Williams fell in love with baseball at an early age and grew to become a 6-foot-4, 200-pound man with a fierce fastball and a pitching acumen to rival any of his white counterparts whose skin color allowed them to play in the major leagues. Williams pitched for more than two decades (1910-1932) in the Negro Leagues from Texas to the East Coast and is famous for hurling five no-hitters. He struck out 27 batters in one 12-inning contest against the Kansas City Monarchs in 1930 and surrendered only a single hit.

The right-hander had a fastball so powerful, it earned him two nicknames, “Cyclone” in the earlier stages of his career, and, later, “Smokey” Joe Williams.

“Someone gave me a baseball at an early age and it was my companion for a long time,” Williams said in a 1950 report from a New York-area media outlet the Hall of Fame was unable to identify. “I carried it in my pocket and slept with it under my pillow. I always wanted to pitch. It was my good fortune to get a job pitching on a semi-pro club in California in 1908 and I kept on pitching until I retired.”

An article in the Seguin Enterprise newspaper from April 1930 previewing what is believed to be one of Williams’ final trips to San Antonio to play ball speaks of his outstanding talent. Williams was 44 then and serving as a player-manager for the Homestead Grays. The article says that “Years ago before he left this city he drew large crowds both white and colored to watch him pitch a game,” the article stated. “He throws like a rifle shot.”

Williams began his professional career playing for the San Antonio Black Broncos in 1905, compiling 28-4, 15-9, 20-8, 20-2 and 32-8 records, according to records from the Hall of Fame. He pitched in an era when relief pitchers were rarely used and starters were expected to finish even games that went into extra innings. On their off days from the mound, pitchers played in the field or pinch hit as professional rosters and payrolls were considerably smaller than they are now. Williams played in the outfield and over time also became a solid hitter.

He later played for the Chicago American Giants, the New York Lincoln Giants, the Brooklyn Royal Giants, the Pittsburgh Homestead Grays and the Detroit Wolves at the end of his career. He spent all or part of 12 seasons with the New York Lincoln Giants, which is the club listed as his primary team on his plaque in the Hall. He also played winter ball in Cuba for several years.

Williams might be best remembered for his performances against major league teams in exhibition games. He went 20-7-1 in those games and threw 12 shutouts, often victimizing other Hall of Fame pitchers such as Walter Johnson, Rube Marquard and Grover Alexander in the process. He once struck out 20 New York Giants in an exhibition game. According to his Hall of Fame biography, former hit king Ty Cobb once described Williams as “a sure 30-game winner in the major leagues.”

There are two names in the conversation when talk turns to the greatest Negro Leagues pitchers — Williams and Satchell Paige. A 1952 poll of former players and journalists in the Pittsburgh Courier named Williams the best player from the Negro Leagues. Williams won by a single vote, 20-19, over Paige.

Thousands of articles, books and movies have documented the lives and accomplishments of Cobb and other white players from Williams’ era while only basic information exists about the careers of Williams and other great black players. In preparing for his induction in 1999, Hall of Fame researchers had a difficult time even verifying the dates of Williams’ birth and death and where he was laid to rest.

The Hall was unable to locate any living relatives at the time of Williams’ induction, but members of his extended family have been identified in the years since. His childhood home in Seguin remains in the family.

His mother (Lettie Williams) is probably better known than Joe, she was born a slave and after emancipation, she grew up here and lived out her life in Seguin.

Williams worked as a bartender post-baseball, one of them is now a soul food restaurant in Harlem. He died on Feb. 25, 1951, from what is believed to have been a stroke just a year after he was honored at the Polo Grounds for his achievements in baseball. Williams never played in the major leagues, but he lived long enough to see Jackie Robinson and other black players finally break down the barrier that had stood in their way for decades.